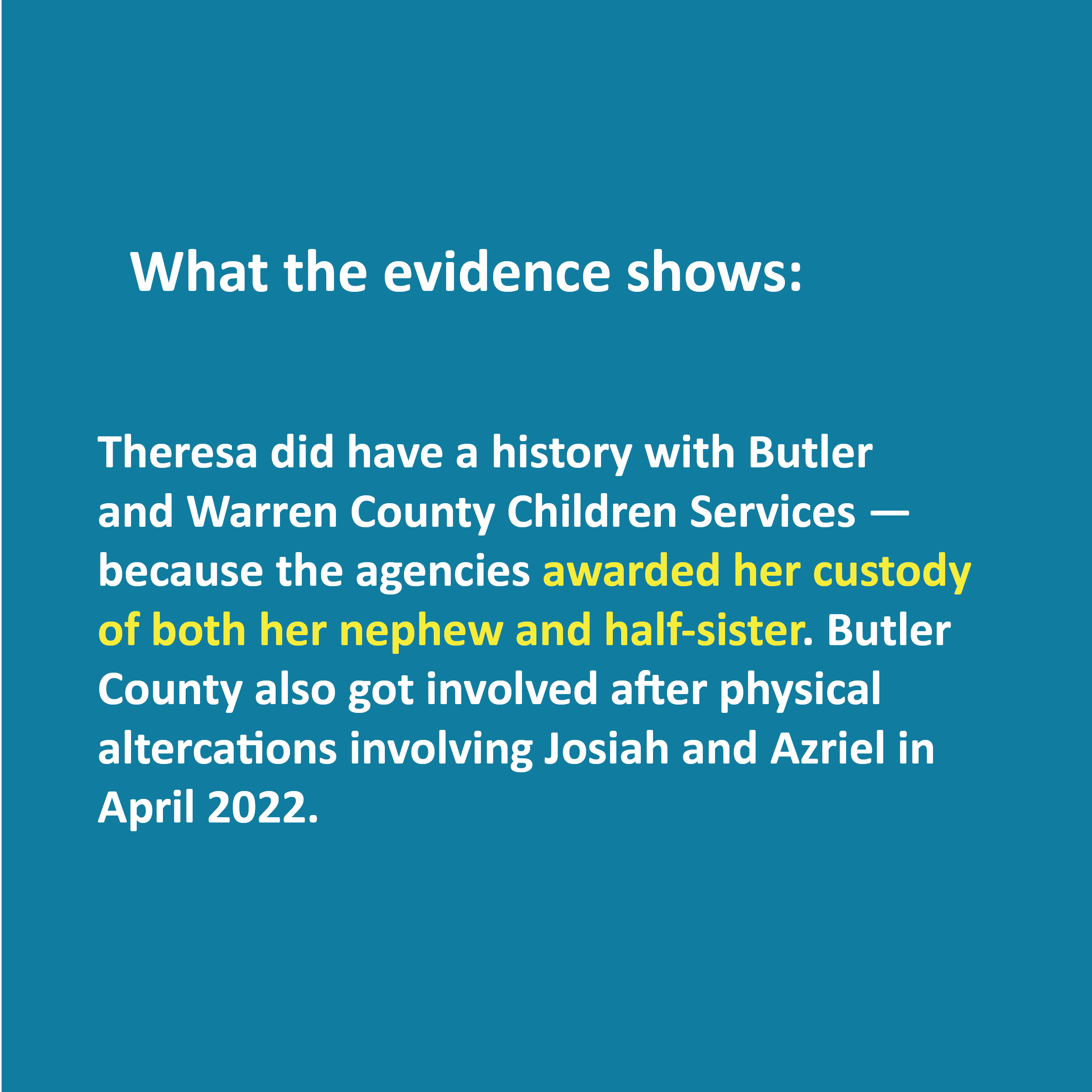

The list of allegations a caseworker said placed Theresa Fogel’s four children in immediate danger and required an emergency removal.

Chapter 3

The investigation

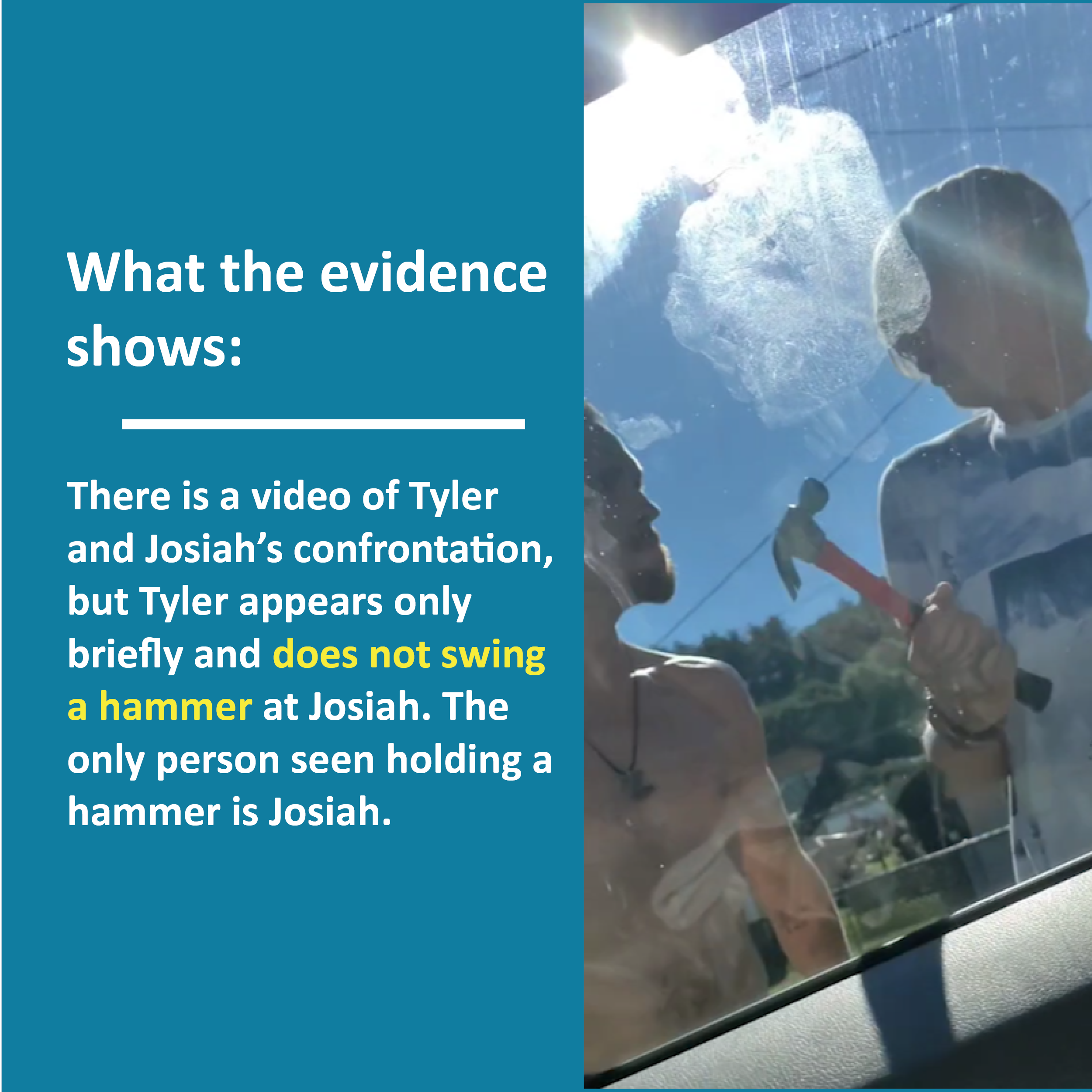

One of the reasons Theresa Fogel was given for the removal of her children is that her boyfriend swung a hammer at her older son.

This was caught on a video that Theresa posted to social media, Jacelyn McGaughey, the Athens County Children Services caseworker who removed the children under an emergency court order, said in a sworn statement.

The hammer incident is the first in a list of allegations that McGaughey said placed the children in immediate danger.

But the video does not show Theresa’s boyfriend swinging a hammer at her son.

Other allegations on the list also have no evidence to support them — or at least none was presented by the agency. Most of them were based on statements made by Theresa’s two boys, and it’s unclear what efforts were made to verify them.

WOUB’s investigation — based on public records and other easily accessible documents, much of which Theresa had on hand and was anxious to share — found evidence suggesting that most of the allegations either lacked support or were simply untrue.

Theresa’s boyfriend, Tyler Tingley, appears in the last two seconds of the video. In the first 45 seconds, her older son, Josiah, is standing outside her car with a hammer in his hand, demanding she turn his cell phone service back on. He raps on the front passenger window a couple of times with the hammer. Theresa is inside the car with her younger daughter recording this with her cell phone.

Tyler enters the frame from the left. Both of his arms are pointed down and remain that way. His hands are not visible. Tyler steps toward Josiah, who takes a couple of steps back. Tyler also steps back, and the video ends.

Content warning: This video contains explicit language.

Tyler acknowledged he had a hammer in his hand when he approached Josiah. He said he had been pounding nails with it when the incident began. He said he never swung the hammer at the boy.

“I ran up. I didn’t lunge. I ran up,” Tyler said. “I said, ‘Get away from your mom’s car. Quit talking to her like that.’”

Theresa said she did not see Tyler swing a hammer at her son.

Theresa posted the video to her Facebook page. McGaughey said Josiah showed it to her when she met with him and his brother at the Glouster library a few hours before she got the emergency order to remove the children.

McGaughey testified in court that just as the video ends Theresa can be heard yelling at Tyler to stop.

Theresa does not say stop or anything like that as the video ends. She shouts “Hey!” Theresa said this was directed at both Tyler and Josiah.

Another allegation in support of the removal is that Tyler threatened to physically harm Azriel and Josiah and threatened to kill Josiah. McGaughey testified that Tyler had threatened to get a shotgun and shoot him. This is what Josiah told her, according to her case notes.

If this was investigated, it did not include talking to Tyler, the source of the alleged threat. He said no one from Children Services ever talked to him about this. No one came to the house to search for a shotgun or any other weapon.

“I didn’t threaten him with no gun,” Tyler said. “I mean, with what gun? I’m a felon. I can’t have guns.”

Tyler served three years in prison for residential burglary. He was released in 2018.

“I don’t tolerate guns,” Theresa said. “There’s no guns in my house. Never will there be a gun in my house, either.”

No evidence was presented to support this allegation, other than Josiah’s statement, and it did not come up again after the first court hearing.

Under Ohio law, removal is warranted only when necessary to prevent immediate or threatened physical or emotional harm. The two allegations involving Tyler are the only ones that arguably placed the children in immediate danger.

Food and shelter

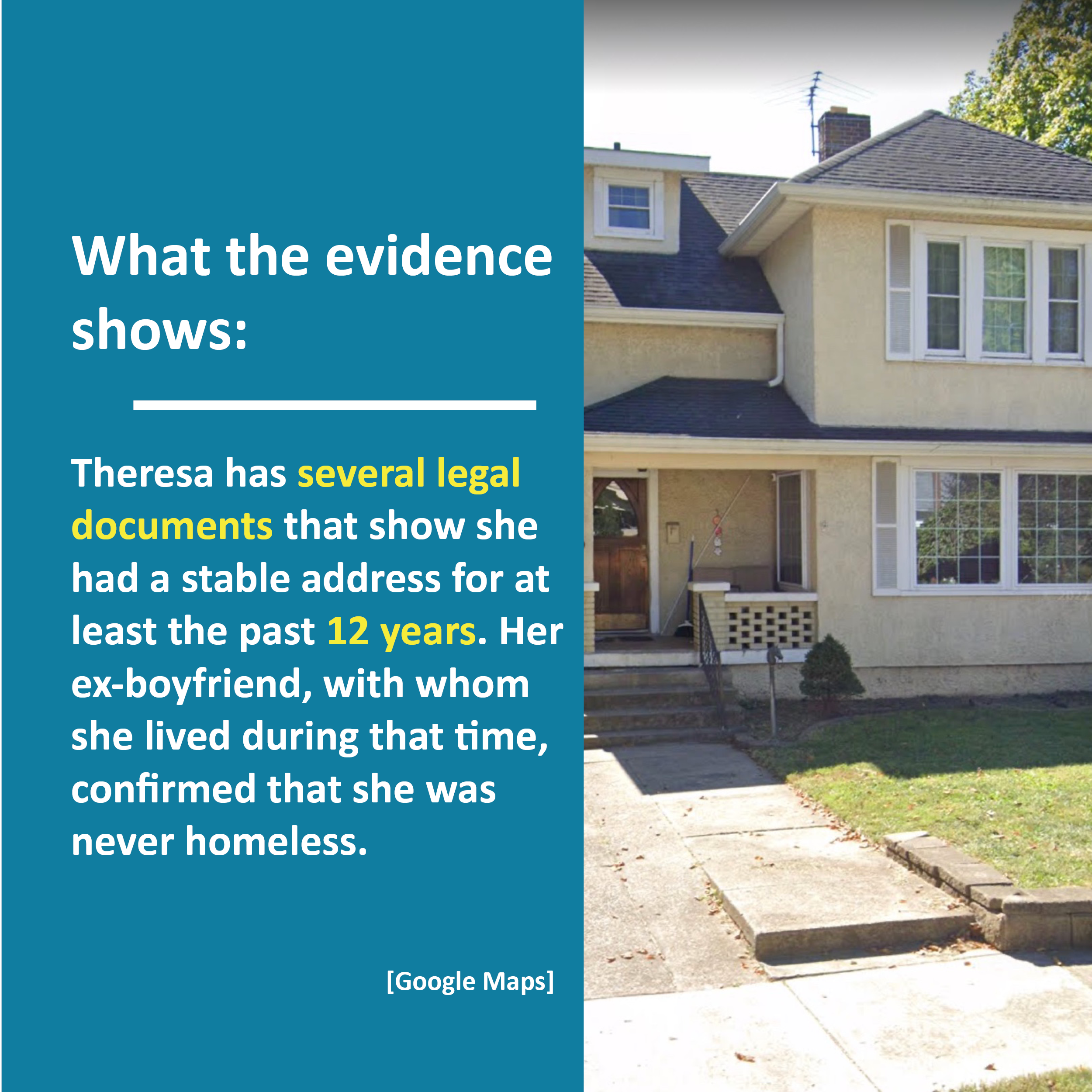

Also on the list of allegations is that Theresa and her children were at risk of losing their home and have a history of being homeless and transient.

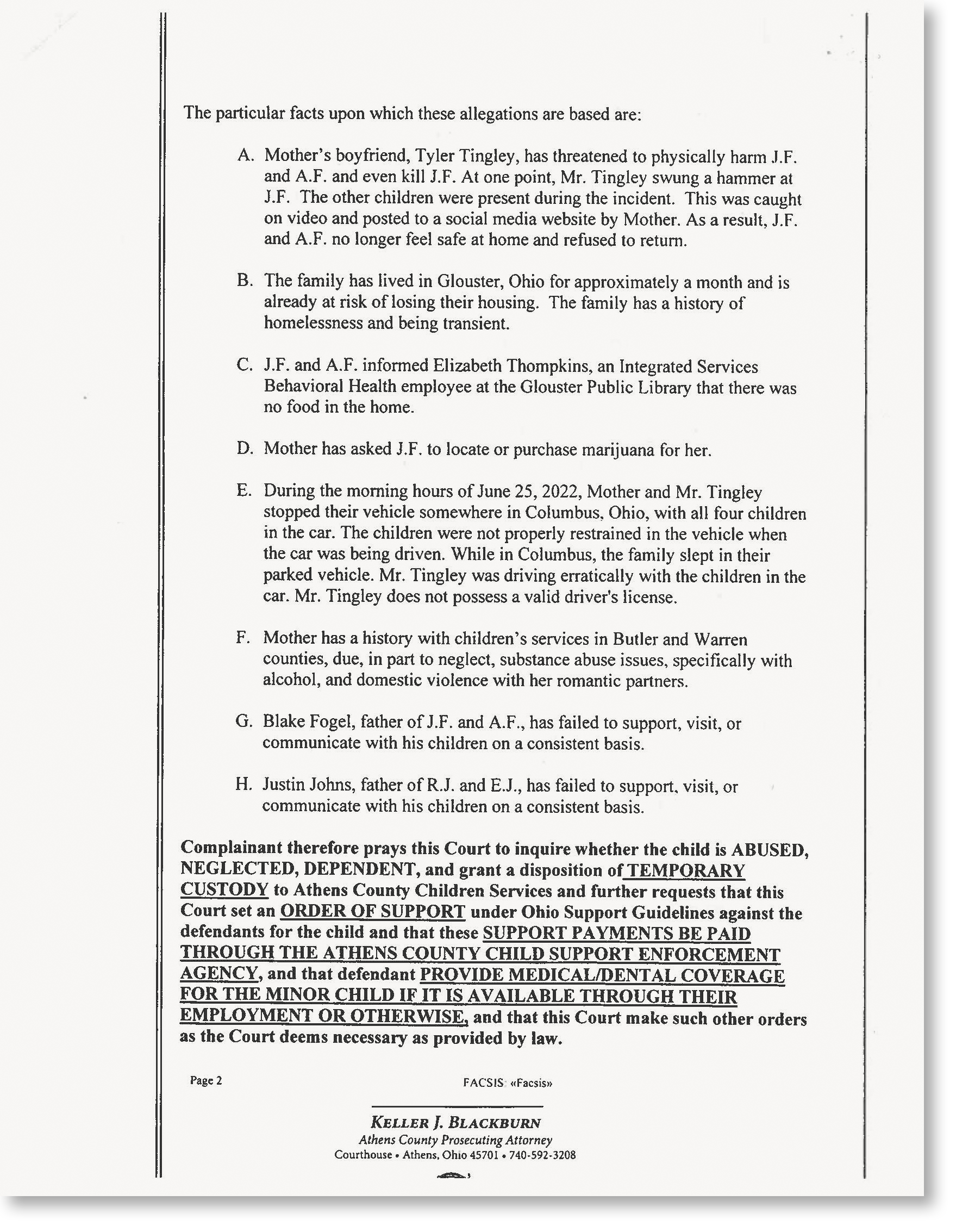

Theresa was facing a possible eviction from the home she was renting in Glouster, just one month after moving in. This was in part the result of a dispute with the landlord. Tyler had been hired by the landlord to maintain his rental properties, and the pay for this work would have been more than enough to cover the rent. But relations with the landlord turned sour as Theresa and Tyler ran out of money before his first payday.

On June 21, four days before Theresa’s children were removed, the landlord gave Theresa and Tyler three days to leave the rental home. But he did not enforce this deadline and let them stay longer. Theresa had already turned to a local legal aid attorney, who was helping to make arrangements for a community action agency to cover the rent for a few months while she and Tyler looked for work.

Theresa’s landlord gave her and her live-in boyfriend, Tyler Tingley, an eviction notice on June 21, 2022. He gave them three days to leave but they ended up staying another two months.

Theresa said she and her children have never been homeless or transient. It’s not clear why the caseworker made this allegation — whether it was something Theresa’s boys told her or it came from another source. Theresa has housing documents, school documents, court documents, documents from social services agencies and more to demonstrate she has had stable housing going back over a decade.

Theresa and Justin Johns, the father of her two girls, moved in together in 2010. They lived in an apartment for a year then rented a home for the next seven years before Justin bought a house in Middletown and they moved in there.

Justin confirmed he and Theresa lived together in these homes until they broke up in July 2020. Theresa continued to live in the Middletown home until Justin filed to evict her, which is when she moved to Glouster.

Court records from Theresa’s divorce in 2009 back this up. Following the divorce, there were issues with custody and child support payments that kept the case active. Over the years, the court sent Theresa documents by certified mail to the homes she shared with Justin.

In January 2018, Theresa filed for custody of the baby boy who had been left at her home a few days after the previous Thanksgiving. This began a process that involved background checks and regular home visits from caseworkers, nurses and others over the next several years. The boy had significant medical and developmental issues Theresa had to attend to, on top of raising her own children.

A judge awarded permanent custody to Theresa in January 2021, noting that she had consistently addressed the boy’s health and safety needs “from day one.” A caseworker testified that the boy had bonded to Theresa and called her mom.

Meanwhile, Theresa’s half-sister, then a minor, was placed with her three times in different years. This also included background checks and home visits by a caseworker.

None of this would have happened if Theresa was, or was at risk of becoming, homeless or transient.

If Theresa was ever homeless, no evidence was presented to show this.

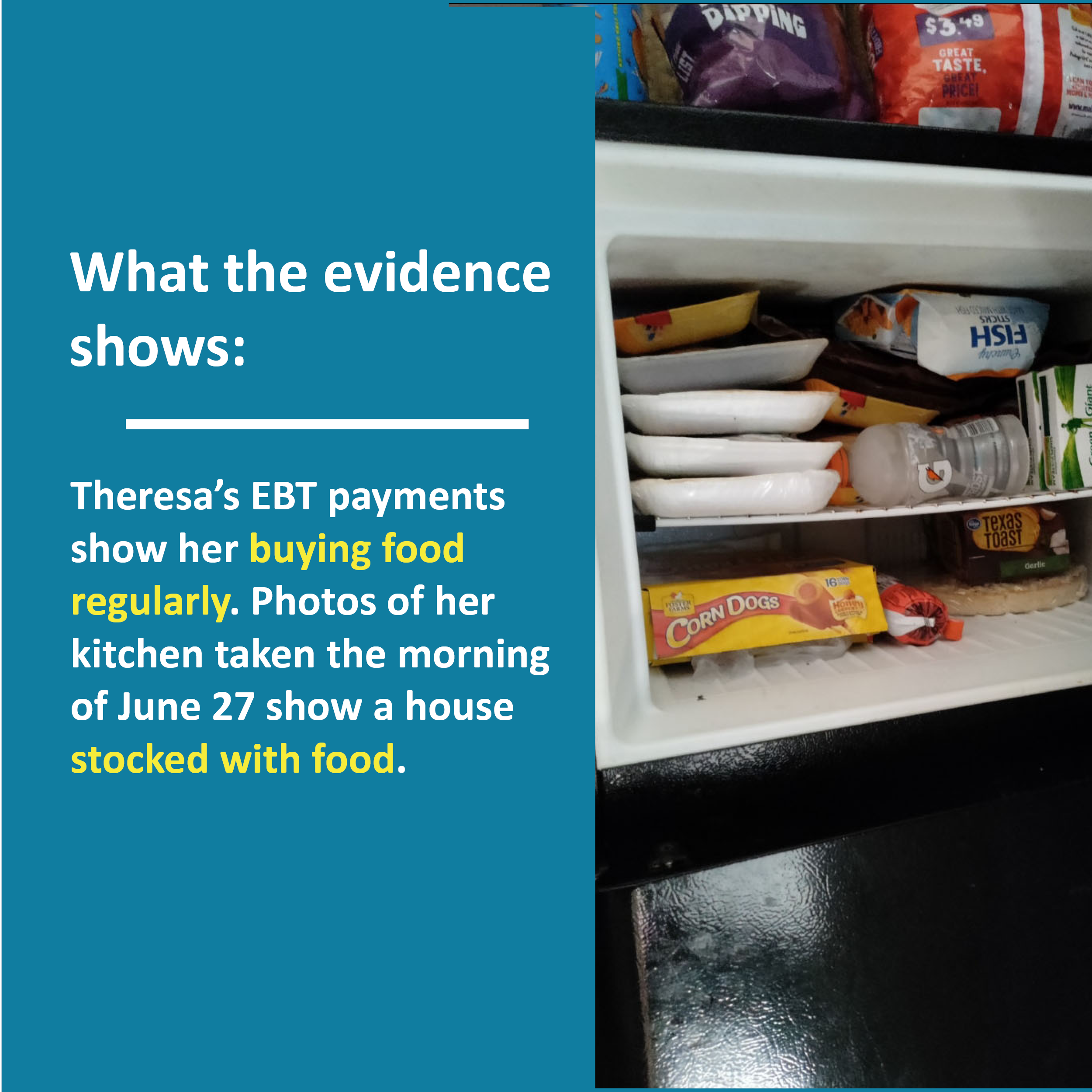

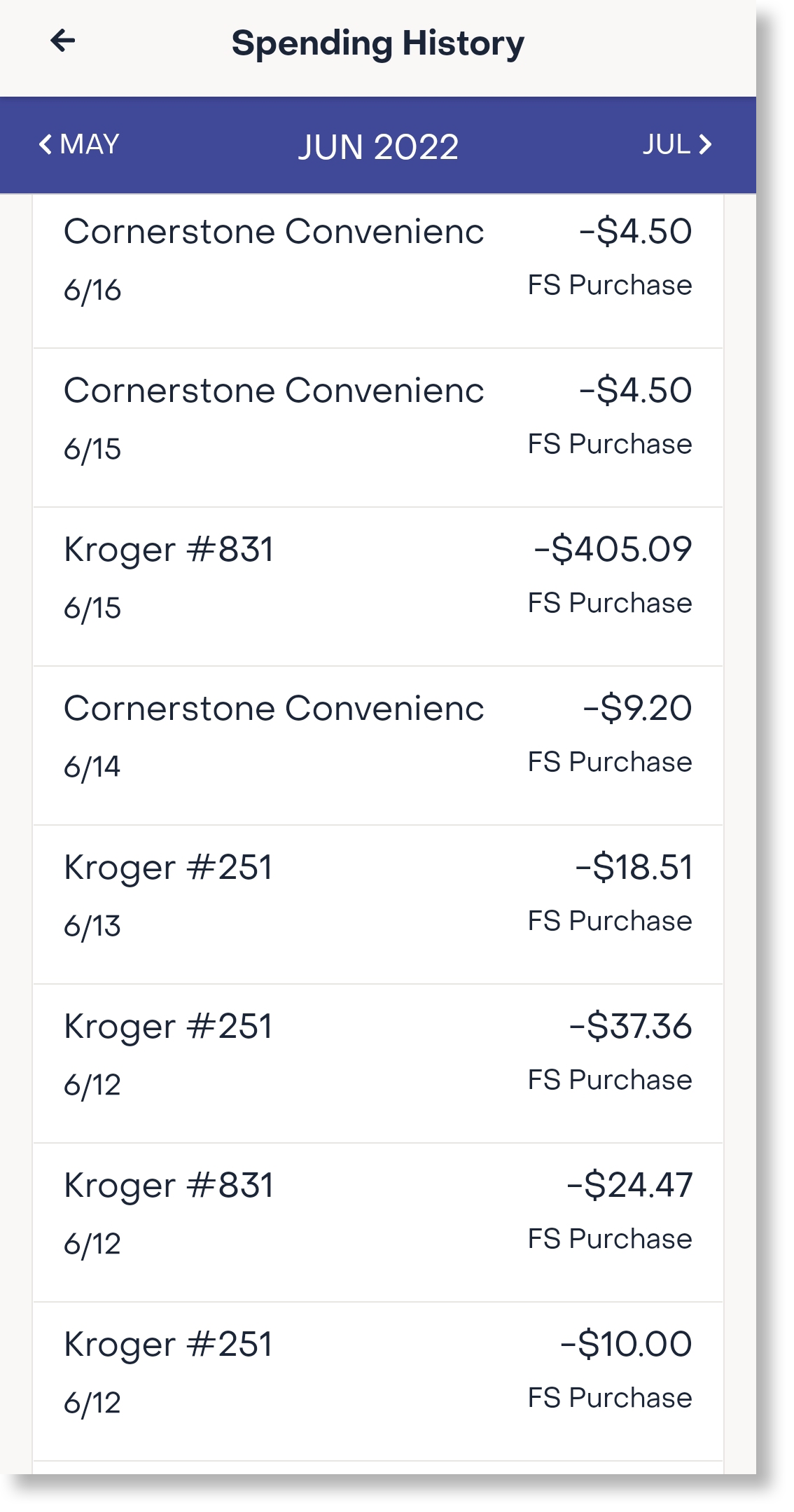

Theresa’s boys told caseworker McGaughey there was no food in the home, another allegation she said placed the children in immediate danger.

No evidence was presented to support this. Theresa and Tyler did run out of money soon after moving to Glouster and could not afford to pay their rent and other bills.

But they had money for groceries because Theresa was receiving $956 a month in federal SNAP benefits, which can only be spent on food.

“I brought so much food with me from our other house that I didn’t know how we were going to fit it all,” Theresa said. While unpacking their things at the Glouster home, Theresa snapped a picture on May 27 of a neatly organized and nearly full kitchen pantry and texted it to Tyler with a message about how she was running out of room.

A page from Theresa’s SNAP account shows she spent several hundred dollars on groceries in mid-June, a week before her children were removed. Her sons alleged there was no food in the home.

Theresa’s online SNAP account shows that after arriving in Glouster on May 25, she spent nearly $500 during the last six days of the month.

She spent $944.72 in June, almost all of this before her children were removed on June 25.

Theresa thinks she knows why the boys would have complained to the caseworker that there was no food. They had grown accustomed to eating out a lot before the move to Glouster.

“Yeah, that’s what they want, fast food,” she said. “And it’s my fault. I have spoiled them.”

“I’ve given them everything they’ve ever wanted and needed,” she said. “So when all of a sudden life comes crashing down … we can’t hand them everything that they want right then. We can’t go to McDonald’s five times a day. We can’t go … ‘We want you to take us here and there. We want you to buy us this and that.’ When I can’t all of a sudden do that, I’m a horrible mother.”

Poverty and parenting

The allegations involving Theresa’s housing and food situation present a larger issue. The vast majority of parents who end up in the child welfare system are poor. Removing their children because of housing or food insecurity raises the question of whether they are being penalized for being poor.

“Children services often conflates poverty with neglect and dependency,” said Kelli Jelinger, a public defender in Erie County who for many years has represented parents in child removal cases. “Being poor does not make you dependent. Being poor does not make you a neglectful parent. It makes you poor. Doesn’t mean that you’re a crappy parent. It just means that you’re poor.

“But children services and courts have long held, ‘Well, we have to step in and care for these babies. We have to step in and care for these children. They can’t do it. They deserve to be where they can be taken care of.’”

Parents struggling to keep a roof over their heads or put food on the table may not be abusing or neglecting their children in the legal sense. But the children can still be removed if they are considered dependent.

The definition of dependency under Ohio law is broad and subjective, allowing children to be removed if their “condition or environment is such as to warrant the state, in the interests of the child, in assuming the child’s guardianship.”

Richard Wexler of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform said he considers Ohio’s definition of dependency among the worst “in its sheer breadth, in its invitation to confuse poverty with neglect.”

Another question raised by these allegations is whether housing and food insecurity place children in the kind of immediate danger that justifies removal.

“A family being homeless and not able to provide food for their children is something that happens over time. It’s not, ‘Someone was chasing me with a gun.’ That’s an emergency,” said Matt Starkey, public information officer for Athens County Children Services. He said his agency tries to help parents in this situation by connecting them with resources in the community that can help with rent and groceries.

While this may be the agency’s policy, it is not what happened in Theresa’s case. When caseworker McGaughey was asked in court whether she tried to provide any services to Theresa’s family, she said she did not because of the emergency nature of the situation.

McGaughey may have been referring to the allegations against Tyler, the boyfriend, which if true suggested he may have violent tendencies. She may have been referring to the fact that when she showed up and suggested removing the children from the house for a while, Theresa refused and drove off with her daughters.

Under Ohio law, it is precisely in emergency situations, when children are considered to be in immediate danger, that caseworkers and their agencies are supposed to at least try to work together with parents to come up with a plan to address the concerns.

“Some people just need a little extra help,” Starkey said. It might be a single mother who is homeless and struggling to feed her children. “Rather than saying, ‘Find a home or else we’re taking your kids,’ we’ll say, ‘We can develop a safety plan with you.’”

“We say, ‘Hey, we can connect you with services to get you housing. We can connect you with services to get you food,’” he said. “In that instance, a lot of the time the children can stay with the parents, or mother, or whomever, because we go out and see she loves her kids. She’s taking care of them the best she can.”

Again, it seems this did not happen in Theresa’s case. She said no one from the agency ever talked to her about the food and housing allegations. This may be because the agency soon discovered Theresa was not facing immediate eviction and had already taken steps on her own to find help with paying the rent, and that she had money for groceries and was spending it on them.

Many families end up in the child welfare system because of some incident that on the surface may not seem related to poverty but in fact is a symptom of poverty, said Jennifer Renne, a national expert who advocates for reform and trains judges and attorneys on ways the system can better help families.

“One of the problems is we focus on the maltreating incident without looking at the whole universe of information that’s relevant to this family,” Renne said. “In other words, the maltreating incident happened and there’s a reaction on the part of social services, sometimes on the part of the judge, to react to the … incident instead of looking at, how’s the family functioning?”

Athens County Juvenile Court Judge Zach Saunders said he tries to be sensitive to underlying issues of poverty that land parents in his courtroom.

“Poor doesn’t equal bad parent. It doesn’t,” he said. “And when I get involved with a case that involves an individual, whether it’s housing stability, food stability, I’ll work tooth and nail to find resources with them.”

But by the time he sees the parents, their children have already been removed, possibly for things that could have been addressed with the resources he wants to help them find. At this point, it will likely take them several months or longer to get their children back even if they get the help they need.

And while there may be awareness within the child welfare system that conditions of poverty do not equate to bad parenting or put the children in immediate danger, the fact remains that most parents whose children are removed are poor.

More allegations

The remaining allegations against Theresa either lack support or it’s difficult to see how they placed the children in the kind of immediate danger that justifies removal.

One is that Theresa asked her older son, Josiah, to locate or buy marijuana for her. Theresa denies this. Her son Azriel said he used his mom’s phone to send the message to his brother. The agency did not present any evidence in support of the allegation.

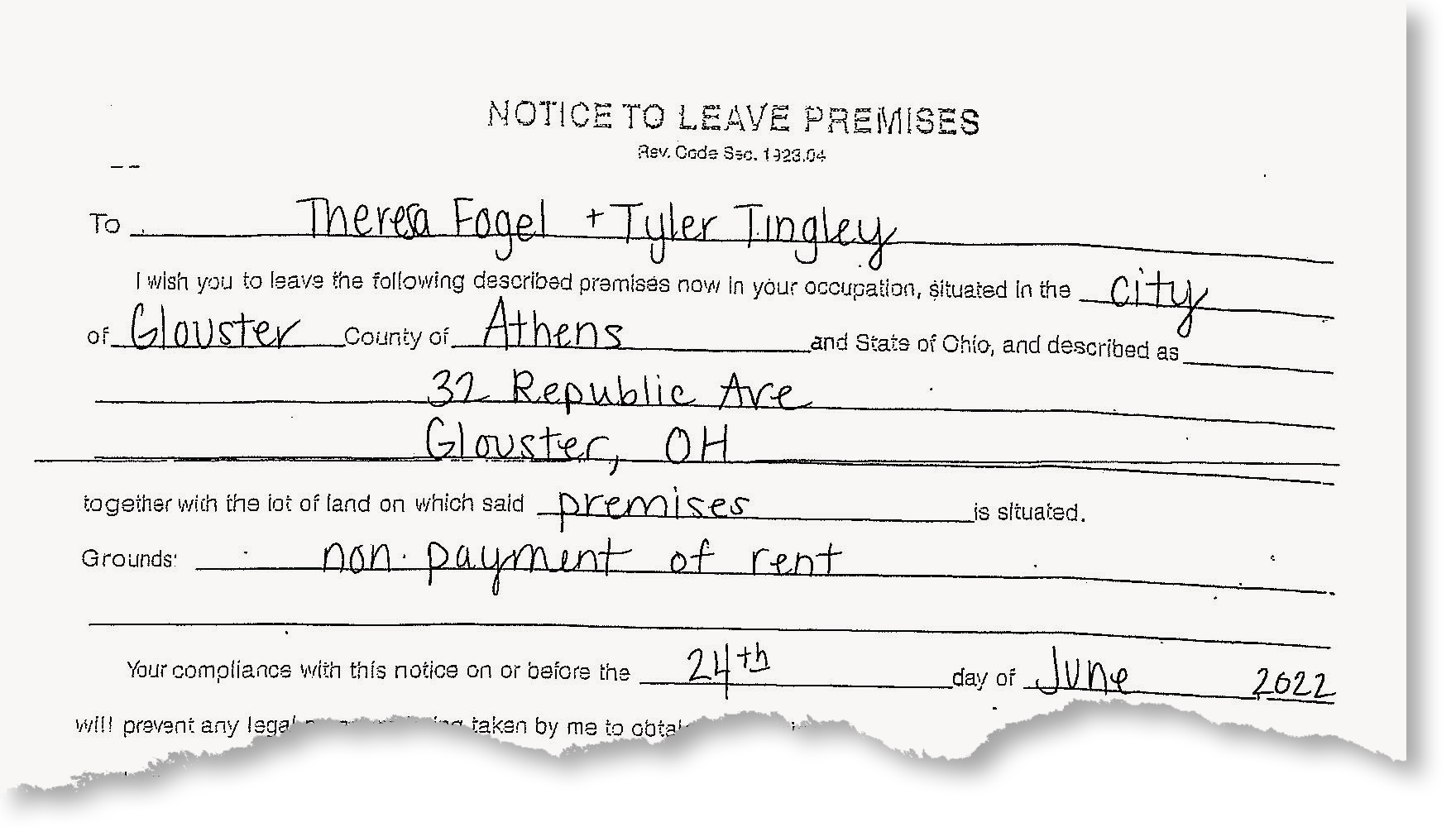

Theresa’s history with the children services agencies in Butler and Warren counties is also among the allegations. Asked about this in court, caseworker McGaughey said she did not have any details, and none were presented later.

She did raise a concern that one of the Butler County cases was closed on May 9, 2022. This was one day after Theresa signed the lease for the rental home in Glouster. McGaughey said that when a case is under investigation and the family moves out of the county, the case has to be closed.

“So it’s concerning that they were moving during an active investigation and so the case had to be closed pretty quickly,” McGaughey said.

Theresa said the case McGaughey was referring to was the incident when she pressed domestic violence charges against Josiah. This was after the two of them got into an argument over his relationship with her 17-year-old half-sister and he shoved her and slammed the door on her foot.

Theresa said she dropped the charge against Josiah right after signing the lease in Glouster on May 8 because there was no point continuing the case against him with the move coming up and what she hoped would be a fresh start for her family.

The one allegation Theresa doesn’t entirely dispute is that while driving home in the wee hours of the morning on June 25 last year, the day her children were removed, she got tired and asked Tyler to drive. He did not have a license at the time.

Theresa does dispute that Tyler was driving erratically, which is what Josiah told the caseworker.

More hearsay

Allegations of abuse, neglect and dependency made against parents are supposed to be investigated.

This should begin with the safety assessment, before any decision about removal is made. But if a safety assessment was done in Theresa’s case, it did not involve going to her house and talking to her and Tyler about the allegations. Theresa and Tyler both said that no one from the agency discussed the allegations with them and asked them for their side of the story.

“Who are you to say there’s no food in my house when you haven’t seen that there’s no food in my house?” Theresa said. “Who are you to say that there’s guns in my house, when you didn’t come in here and look for guns in my house? Who are you to say any of these things if you didn’t come and look for yourself?”

The investigation would continue if a safety plan is being developed, which should involve talking to parents about the things that are placing the children in immediate danger and coming up with ways to address them. But it appears the safety plan presented to Theresa — removing the children and placing them with relatives or in foster care for a while — was developed without her input.

Saunders, the Athens County judge, said it’s his expectation that by the time a caseworker is coming to him for an emergency order to remove children an investigation has already begun and the agency has more than hearsay evidence to support its claim that the children are in immediate danger.

“Because if they went off with simple allegations without trying to confirm some aspects of that, then there would be a problem,” he said.

Hearsay is something someone said outside of court that is being used as evidence in court. It’s generally not allowed.

Hearsay appears to be the only evidence the agency had to support most of its allegations against Theresa. If the agency had anything more than statements made by Theresa’s sons, it was not presented in court or in any court documents.

The investigation is supposed to continue after a removal as the agency prepares to defend its action in court, but also to make sure that additional evidence uncovered continues to support the removal decision.

It’s unclear how much investigation was done after Theresa’s children were removed, and at what point the agency discovered how little support there was for the allegations other than the boys’ statements.

McGaughey, the caseworker, was not available for an interview. Even if she was, she would not have been permitted to discuss the details of Theresa’s case because of confidentiality rules.

Mimi Shuttleworth, who lived two houses down from Theresa, said she was surprised no one talked to her or the other neighbors as part of any investigation. Shuttleworth was an Athens County sheriff’s deputy for several years and has spent most of her career as an investigator for the state Bureau of Motor Vehicles.

Shuttleworth said she and the other neighbors kept a close eye on Theresa’s family given a long history of bad tenants in that rental home. She said she would watch them out her window and talked regularly with the neighbor next door to Theresa to compare notes.

One day she saw them carrying in a lot of grocery bags from Kroger. She saw them out in the evenings cooking food on the grill.

“They had no idea the microscope that they were under when they moved into that house,” Shuttleworth said. But she and the other neighbors liked what they saw.

“I mean, we were utterly amazed that this is a decent family that we got in here for a change,” she said. “And then when all this went down, we were all looking at each other. How could that happen? What, what happened here? What did we miss? And we don’t think we missed anything. We all believe that children services failed to do their job.”

Working through the process

What Theresa’s case shows is that whether the allegations against parents are true may not matter much in cases of removal.

If the allegations are false, this may not be discovered depending on how thorough the agency’s investigation is and how much work the defense attorney is putting into the case.

And even if it is discovered, it may not make any difference.

Parents whose children are removed under false allegations may have to go through the same process to get their children back as parents in cases where the allegations are true.

Theresa said McGaughey may have hinted at this when they met briefly at the courthouse before her first court hearing.

“Jacelyn pulls me into a room, and she was like telling me that Josiah’s so manipulative and I’m going to get my kids back as soon as I can, but they have to do their job,” Theresa said. “I’m like, ‘You literally just told me my child’s manipulative, which is the whole reason I called the police in the first place, and now you’re telling me, but what? I can’t have my kids back? What did I do wrong?’”

Judge Saunders acknowledged that when children are removed, it sets in motion a legal process with its own timeline. Asked how long it would take parents to get their children back if the allegations that triggered removal are false, he said at least a month and maybe longer depending on whether there are any delays in the process.

“When the system works, it works,” Erie County public defender Kelli Jelinger said. “When it doesn’t work, the ones that suffer are the kids who are supposed to be the ones being helped, yet they’re removed from parents that love them, that may not be perfect.”

To many of those advocating for reform of the child welfare system, focusing on whether the allegations against parents are true misses a larger point.

“Even if every one of the allegations you have mentioned were true, it wouldn’t be grounds to remove,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “We’ve talked about lack of food is grounds to call a food bank, lack of housing is grounds for a rent subsidy. And if a boyfriend is swinging around a hammer and engaging in assault, that’s grounds to remove the boyfriend from the home. There is a method for that, it’s called arrest. And there is a placement available, it’s called jail.”

Wexler and others inside and outside the child welfare system argue that in too many cases, removing a child from a home is not the last resort it is supposed to be.

“When the system works, it works. When it doesn’t work, the ones that suffer are the kids who are supposed to be the ones being helped, yet they’re removed from parents that love them, that may not be perfect.”

— Kelli Jelinger

Erie County public defender

In most cases that get screened in by a child welfare agency, there is some truth to the allegations. But in many cases there are other options besides removal to address the concerns, said Jennifer Renne. She worked for years handling these cases as a defense attorney. She now advocates to improve outcomes for children and parents in the system through her work with the American Bar Association’s Center on Children and the Law.

Renne said part of the reason so many children are removed when there may be other more helpful and less disruptive options is there is something about the culture inside the child welfare system that is punitive.

“I say to people all the time: It’s not us and them,” said Renne, who travels around the country training attorneys and judges who work in the system. “It’s not those families. It’s all of us.”

This punitive orientation extends to the public, she said, especially in cases involving abuse or neglect where people want to see parents punished for the bad things they did. She said it’s harder to understand these may not be bad people or even bad parents but parents dealing with stressors in the family that lead to these problems.

Part of the challenge for child welfare agencies is many are not well integrated with support services in the community, Renne said. Instead of identifying needs and connecting families with services as an alternative to removal, agencies too often remove first.

There are times when removal is appropriate, Renne said. But even in those cases it’s taking too long to get the children back home, which she said causes more trauma for the children and their parents.

A one-sided affair

Theresa’s first opportunity to challenge the allegations against her was at the court hearing two days after her children were removed.

But when Theresa arrived at the Athens County Courthouse on Monday, June 27, she had two things going against her.

One, she had no attorney. Two, whether the emergency removal of her children was justified would be judged by a probable cause standard, the lowest standard for a court hearing.

The hearing goes by various names: probable cause hearing, emergency custody hearing, shelter care hearing. Its purpose is for a judge to determine whether the children should remain in the agency’s custody. And so, the hearing is also a test of whether the children should have been removed in the first place.

The shelter care hearing must be held by the end of the next business day after an emergency removal and no later than 72 hours after the removal order was issued. This deadline recognizes the seriousness of taking children from their home, but it also allows little time to prepare for the hearing.

The children services agency is represented at the hearing by a county prosecutor, who can present evidence and call witnesses to the stand and question them under oath. Parents can do the same.

Theresa’s hearing was before Judge Saunders, a former prosecutor who previously worked in private practice and represented parents in child removal cases.

It was Saunders who gave caseworker McGaughey permission to remove Theresa’s children. Emergency removals require a judge’s consent.

“It’s not easy, ever,” Saunders said. “The last thing I ever want to do is remove any kids. And ultimately when it comes down to it, in a nutshell, with the limited information that I have at the time, what’s in the best interest of that child? That’s the tenet that I go to: What is the best interest of this child?”

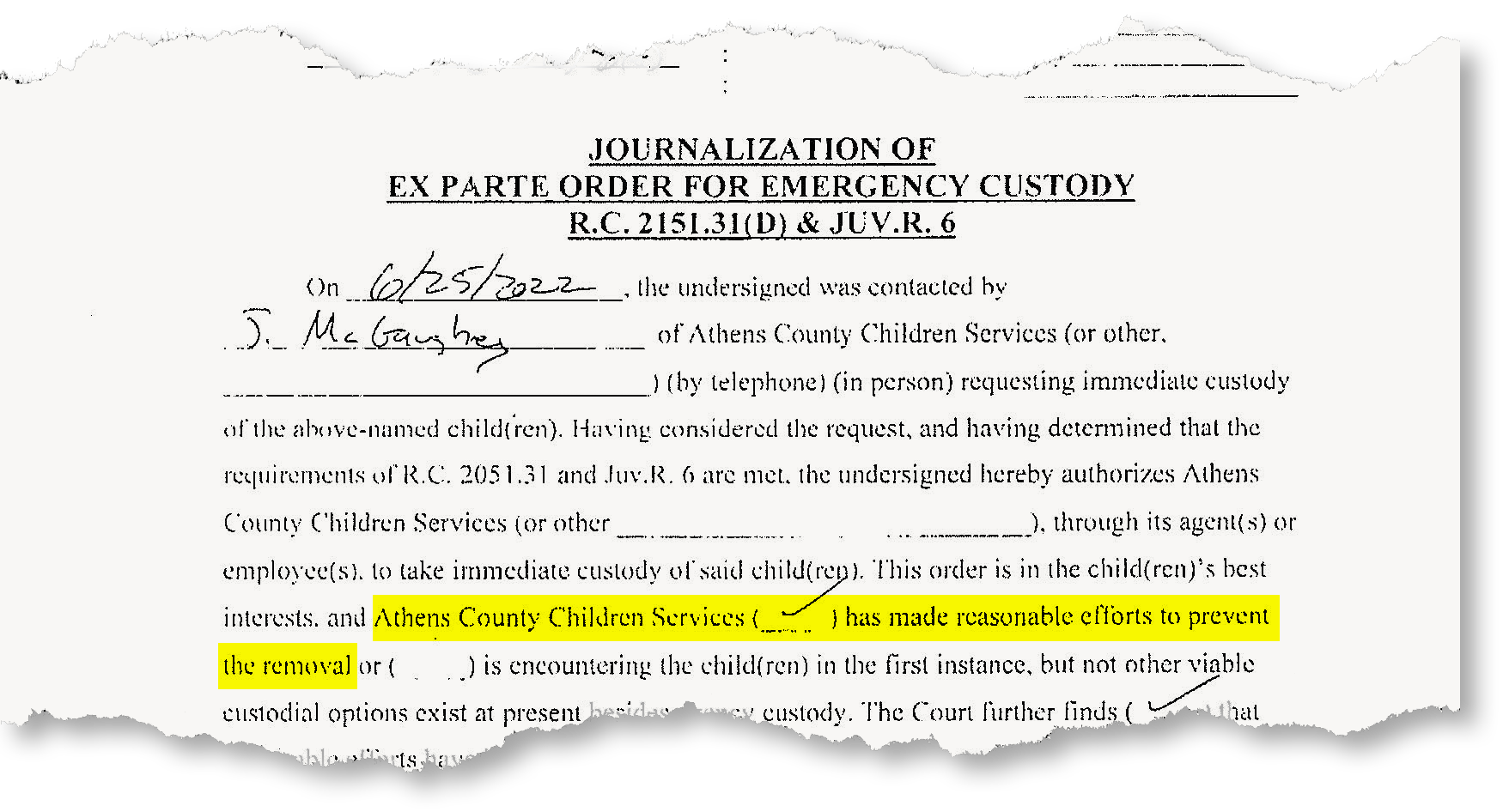

This emergency authorization can be made by phone but it then has to be entered on a form that becomes part of the case file. The form in Theresa’s file has a check next to a statement that says Athens County Children Services made reasonable efforts to prevent the removal.

The emergency court order authorizing removal of Theresa’s children.

Saunders says he always begins a shelter care hearing advising parents of their right to an attorney, and letting them know that if they cannot afford one, the court will appoint an attorney for them, just as in criminal cases.

Theresa arrived at the courthouse an hour before the hearing to allow enough time to fill out the financial paperwork demonstrating she qualified to have an attorney appointed by the court.

She was expecting to have an attorney at the hearing. She would not.

Nearly all of the parents who arrive in Saunders’ courtroom for a shelter care hearing will not have an attorney with them.

This is because almost all of the parents whose children are removed under emergency orders are poor and the court cannot find and appoint an attorney in time for the hearing.

The shelter care hearing will in many cases be the only time parents can challenge the removal. But without an attorney, most won’t know how to do this. The result is the hearing is largely a one-sided affair, with the prosecutor calling all the witnesses and asking all the questions.

With no defense attorney to push back against the removal, it’s even easier for the agency to meet its already low burden to show its actions were justified.

In a few of Ohio’s larger metropolitan areas, child removal cases are handled by attorneys from the public defender’s office, so parents will have an attorney to represent them at the shelter care hearing.

But in most Ohio counties, including Athens, the public defender’s office, if the county even has one, does not handle these cases. Instead, they are assigned to attorneys in private practice. This can be challenging for courts in rural counties like Athens that don’t have a lot of attorneys to begin with.

“That’s what’s killing me right now is that it’s becoming harder and harder to find attorneys that are willing to take these types of cases,” Saunders said.

His office often has to reach well outside the county to find an attorney, making it even harder for parents to exercise their right to have a lawyer at the shelter care hearing and make it a more balanced proceeding.

“I have attorneys that are from Lancaster, from Columbus,” Saunders said. “So, it’s impossible for me to have someone here within that time frame.”

Under the court-appointed model, a parent may get an attorney with a lot of experience handling these kinds of cases or very little. The child welfare system is governed by hundreds of state and federal laws, regulations and policies. Legal experts agree it’s a complex area of law, but there is no requirement in Ohio that attorneys who take removal cases have any particular training.

Judges like Saunders cannot afford to be too picky given how few options they have.

“We have a select few that are always willing to do it, and I appreciate that they’re willing to do it,” he said. “And I know that these cases are tough. They’re hard cases. They take a toll on everybody.”

The lowest standard

Once an attorney is appointed, they can ask for another shelter care hearing, and the judge must grant the request. But this rarely happens, possibly because the hearing rarely changes anything for the parents anyway.

Because removal is judged by a probable cause standard at the hearing, the agency need only show it was reasonable under the circumstances. This doesn’t mean it was the right decision, only that it was reasonable.

“The standard of proof to hold that child in foster care is not beyond a reasonable doubt. Not even clear and convincing. It’s the lowest standard there is,” said Richard Wexler of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

Also, the rules of evidence don’t apply at these hearings, which means that whether the removal was reasonable can be based on hearsay.

This is what happened in Theresa’s case. When the caseworker was questioned at the hearing about the concerns she had that led to removal, she mostly repeated what Theresa’s boys had told her. That’s hearsay because it’s one person’s account of what another person said outside of court.

At a shelter care hearing, this is enough to support a probable cause finding that the removal was justified, without any additional testimony or evidence to support what the caseworker said.

If parents have a lawyer at the hearing, they can at least question witnesses called by the prosecutor and put their own witnesses on the stand to help determine whether the agency made reasonable efforts to avoid removal, whether the allegations underlying the removal are supported by evidence and just how much investigation was done to substantiate the allegations before removing the children.

But given the probable cause standard, the outcome is still likely going to be that the children remain in the agency’s custody. Two veteran public defenders interviewed for this story who have spent years representing parents in child removal cases said they have rarely won a shelter care hearing.

The Athens County Courthouse, where the fate of Theresa’s family was determined after her children were removed. [WOUB | Natalie Colarossi]

It’s easy to see how a children services agency could grow accustomed to not having to worry too much about how much or how little investigation it has done or how much evidence there is to support the allegations before the shelter care hearing.

At Theresa’s hearing, the prosecutor walked caseworker McGaughey through the allegations. Asked what she did to investigate, McGaughey repeated what Theresa’s boys told her.

She was not asked whether she talked to Theresa or Tyler or anyone else about these allegations or what steps she took besides talking to the boys to try to substantiate them.

She was not asked whether she did a safety assessment and whether this involved going to the house and talking to Theresa and Tyler about the allegations.

Asked what she did to avoid removal, McGaughey said she offered a safety plan and Theresa refused it. No questions were asked about how this plan was made and whether it involved substantial input from Theresa.

The shelter care hearing ended with Saunders asking Theresa if there was anything she wanted to say, but cautioning her that anything she said could be used against her.

“And I was like, ‘I’m not saying anything until I have an attorney,’” Theresa said, “and then I shut my mouth. I wasn’t saying nothing.” This is the advice Saunders had offered at the start of the hearing.

Saunders concluded there was probable cause — “a very low standard,” he noted — to remove the children and continue to keep them in the agency’s custody. He also said it did not appear reasonable efforts were made to prevent removal given the emergency circumstances.

It’s not clear what steps were taken by the caseworker, besides talking to the boys, to determine there was in fact an emergency. A good defense attorney may have asked questions about this.

The next hearing would be the adjudication, where parents can request a trial and force the agency to prove the allegations underlying the removal by clear and convincing evidence, a much higher standard than probable cause.

This is what Theresa planned to do. She knew that most of the allegations against her were untrue and she had lots of evidence to share with her attorney to prove this.

She wanted to fight. But things would not go as she planned.

After the shelter care hearing, Theresa’s family was split apart even more.

The caseworker took Theresa’s daughters to a foster home. Theresa would later have to plead with a county sheriff to get her girls out of there.

Her sons were taken to their aunt’s house in Butler County. This was exactly what the older boy wanted. It did not work out so well for his younger brother.