Christy Biehl of the Washington County Homeless Project organizes blankets and other warming supplies at a drop-in center in Marietta for individuals experiencing homelessness. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

A town in southeast Ohio comes around to the idea of sheltering those experiencing homelessness

A Marietta drop-in center has shifted public sentiment, and city officials are now endorsing an overnight shelter. One man shares what it's like being homeless in a small town where everyone knows you.

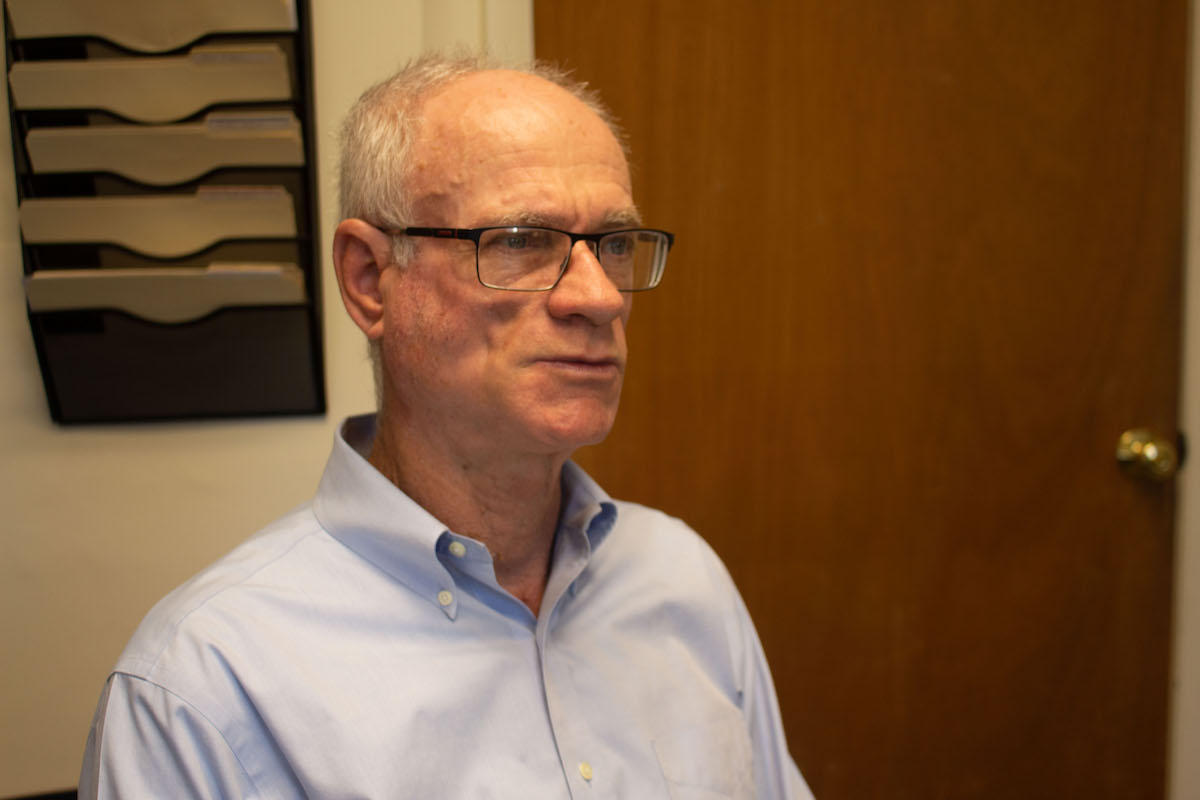

MARIETTA, Ohio — The Washington County Homeless Project drop-in center occupies an unassuming space among the small businesses dotting Front Street, one of the main roads in Marietta’s downtown.

Step inside, and there’s a good chance an excitable shih tzu named Willie will be there greeting visitors in the front lobby. Down the hallway is a storage closet, a dining room, a kitchen and a bathroom with a shower.

It is here that people experiencing homelessness in Marietta can come to wash their clothes and bodies and enjoy a hot meal. If they need blankets or sleeping bags, they can take one from the closet. If they’re having trouble with a government agency like Job and Family Services, there’s a woman here who can help make phone calls.

The Life and Purpose Community Resource Center is the current home of the Washington County Homeless Project drop-in center. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

The one thing the drop-in center can’t do is put a roof over someone’s head at night. The building closes down in the evening, and its visitors must go back to wherever they came from: a tent in the woods, a bench in the park, a friend’s garage.

Like many towns in southeast Ohio, Marietta is coming to terms with a sizable homeless population. While some members of the public blame the issue on drug use or a society-wide decline in work ethic, experts say it comes down to a basic math problem: There are just far more people in need of homes than there are homes to live in, and the gap has been widening in recent decades.

That means some wind up with no home at all.

According to internal records, the drop-in center served 182 unique individuals in 2023. Of those, 111 were classified as actively homeless, while the remaining 71 were at imminent risk of becoming homeless. In that time, the center distributed over 3,500 to-go bags and served almost as many meals in-house. Washington County Homeless Project Chairwoman Robin Bozian estimated there was an average of 18 to 22 visitors per day.

The organization has shared these numbers with Marietta City Council to help local officials understand the scope of the problem.

Bozian said she is a proponent of “housing first”: Put people back in a home right away, and then connect them with services like counseling. This may strike some as counterintuitive, but experts say it gets results. Individuals in housing first programs show greater improvement in substance use disorder and other mental health conditions than those in more traditional “treatment first” settings, leading to fewer people sliding back into homelessness. For this reason, housing first is the prevailing model at the federal level and among many local organizations.

The problem is that there isn’t enough housing in Marietta to support a housing first strategy.

“We just don’t have it,” Bozian said. “If (housing) were available, I think that would be absolutely right.”

Robin Bozian arrives at the drop-in center carrying supplies and the leash of her shih tzu, Willie. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

The issue isn’t unique to Marietta. As the cost of housing rises much faster than wages, rent becomes unaffordable for a growing portion of the population. For those with nowhere else to go, the main way out is the federal Section 8 housing voucher program. But the program is experiencing long waitlists throughout southeast Ohio, and those who do finally get a voucher can’t always find a landlord who will accept it.

“We’ve got two or three people right now that currently have vouchers, but they’re struggling to find a place,” Bozian said.

Section 8 and other affordable housing programs simply don’t have the stock to meet the need. It becomes a game of musical chairs: Someone is going to end up without any housing at all.

Local officials are waking up to the situation, though the response has been uneven. Ross County Community Action recently opened a massive emergency shelter in Chillicothe with support from county commissioners. Organizers in Athens County have met to discuss options for a shelter, but planning is still in its early stages. Meanwhile, Perry County’s commissioners have reportedly voiced opposition to any kind of homeless shelter.

Experts agree the long-term solution is to build more housing. But this requires reversing a decades-long decline in the construction industry’s productivity, which is proving challenging.

Bozian said the difficulty finding housing causes new problems she and her colleagues end up helping to straighten out.

“We spend a good bit of our time working with people, making sure they, for instance, are able to get to appointments,” Bozian said. “I mean, just the simple business of keeping appointments is really, really difficult when you are not living in one place.”

You can't stay here

As an Army kid, Gene saw a lot of America.

He estimates he and his family moved to 15 different bases while he was growing up. His favorite was a naval base in New York where he could see the submarines docked.

“Mom took care of the bills, dad worked for the money,” he recalled. “You know, we was raised right. Just ended up, I dunno, partying too much. One thing led to another.”

At some point, Gene wound up getting in trouble and “doing a bunch of stupid stuff.” It’s one of the few topics he doesn’t like to discuss. After his father died, he couldn’t piece his own life back together.

“Some people just, you know, something happens and it’s a hard time pulling yourself out of the gutter when it does,” he said. “You know, I thought I was on top. Had everything going for me, dude, and then I lost my dad and just went downhill, bud. Didn’t care about nothing, didn’t want nothing. I reached out and asked family for a helping hand. They turned their — they rolled their eyes and walked away. Called me all kinds of names. Blamed me for a bunch of stuff that I had no control over, but I got the blame for it anyway. So I just walked around with it on my shoulders, bud.”

He later added: “I’ve seen all kinds of family in my day. Some of the family I got? Bud, I’d trade ’em all for a poodle.”

“I almost forget what it’s like, sleeping in a bed,” Gene said. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

Carrying a chip on his shoulder became the dominant theme of Gene’s life. He said for a long time, he didn’t care about anything.

Bozian said she sees this kind of thing often.

“What happens with a lot of folks when they’ve been through this for so long is they just have no hope. You know, it’s just, ‘It’s all useless. It’s very, very, very useless,’” she said.

Gene said Marietta’s small-town culture doesn’t help.

“The people around here, they just, they don’t like the homeless. Flat out. And only certain people will actually help us, and certain people won’t,” he said.

“Your name’s one thing around this town that, depending on who you are, (decides) whether somebody wants to help you or not. ’Cause they hold your past against you here. … They know what you had for breakfast this morning before you even got up. They make the — nosy neighbors? No, dude. Nosy town. ’Cause you make it down to the end of the block, everybody knows your business before you do.”

Finding a place to sleep is especially challenging, thanks to what Gene described as hostility from the local police. Fall asleep on a park bench, and an officer might wake you up at 3:30 in the morning.

“‘Move on,’ they say. ‘Move on or go to jail.’ Where the hell would you like me to go, dude?” Gene said. “They tell you to get up and keep walking, bud. Don’t go to sleep, ’cause they’ll wake you up and move you again. They do it three times, they take you to jail.”

Gene said he’s seen some people who deliberately get themselves taken to jail just to be indoors. He’s not one of them.

“Better being out here than being in jail,” he said. “For one, the air quality is better. For two, you ain’t got somebody telling you to get up, do this, get up, do that. You ain’t got a light that stays on and people — you ain’t gotta wake up to people fighting over your head. You know? You’re in a pod with, say, a hundred people. You don’t wanna hear that. Being out here is better. At least you can go walk off. You can go sit under a shade tree. Can’t do that in jail. Ain’t no place to sit.”

Being outside, however, means constantly avoiding the eye of the police.

“They tell you to go hide in the woods somewhere, and when you go do that, try to set up a tent somewhere, they come and kick it down,” Gene said. “They slice your stuff, they kick your tent down, they call you a bunch of names, they tell you to get lost, they tell you you’re on private property. About everywhere around here belongs to somebody.”

“If they tell you, ‘You got 24 hours to move your stuff,’ they mean you got six,” Gene said. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

Sometimes, the only thing to do is keep walking.

“You just walk around ’til you can’t walk no more and you just fall over. And when you wake up, and see where you’re at, you get up and get moving again,” Gene said.

The Marietta Police Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Emergency shelter

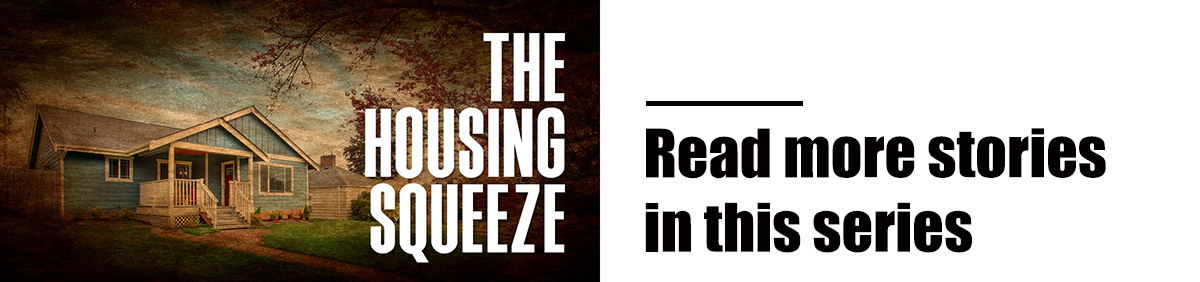

According to Marietta City Council member Harley Noland, the issue of homelessness took on heightened visibility during the winter of 2022-23, when the city opened the old armory so that everyone had a place to sleep indoors.

“There were some problems that came out of that,” Noland said. “Some drug problems, and even some violence. And so everybody says, ‘Oh, we don’t want to be around these folks.’ Well, they were going to freeze.”

The experience did not endear city officials to the idea of further sheltering Marietta’s homeless population. Nevertheless, it did show them just how much homelessness there was in the area.

Bozian, Noland and other advocates got to work on setting up a more organized overnight shelter — one that wouldn’t use city property or city funds. The Washington County Homeless Project would run the facility after it opened.

Efforts ensued to win over Noland’s colleagues on the City Council. Even if they wouldn’t support the project financially, their endorsement could convince others to help fund it.

“One person said, ‘In this community, we have an animal shelter, but we don’t have a person shelter. And we should be equally as humane to our fellow man as we are to pets,’” Noland recalled.

Another community member told city officials she couldn’t live in a place that would let people freeze to death just because they couldn’t take care of themselves.

Marietta City Council member Harley Noland said the city is also looking into improving its rental inspection in an effort to crack down on substandard housing. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB]

“We’ve gotten some really great community support,” Bozian said. “There have been people who have pretty much championed this once we got it going.”

Bozian believes the drop-in center helped change community perceptions of homelessness.

“Once we started operating, people stopped by, they saw what was happening, and they said, ‘Well, this really is a good thing,’” she said.

Before the drop-in center moved to Front Street, it occupied a local parsonage. Bozian said the Washington County Homeless Project agreed to hire retired police officers to keep an eye on things. One of the officers told Bozian he was stunned by how differently some of the individuals behaved when they weren’t on the streets.

“He said, ‘If you had asked me six months ago whether so-and-so or so-and-so would ever be reasonable in presentation … I never would have dreamed that they would be so kind and wonderful and caring,’” Bozian recalled.

Noland has long understood homelessness is more complicated than the stereotypes surrounding it.

“When I owned a restaurant, (we) had one person who we found sleeping under a bridge here in town in the dead of winter,” Noland recalled. “And it wasn’t that he was mentally ill, drug addicted or drunk. It’s simply, he’d been in the military and hadn’t been able to get moneys together to take care of himself. So we got him a job and everything was fine. He’s now a public school art teacher, you know? Finished college and all that.

“I’ve known one other person, a high school student who was being abused in her home, and she removed herself from the home, but had no place to go. So we arranged for her to go to the Betsey Mills Club, which is a place where young women can stay overnight.”

Visitors at the drop-in center take the opportunity to warm up in comfortable chairs. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

Noland pointed to these examples to show helping people who don’t have a home isn’t a waste of time.

“You just have to make people aware that sometimes people need help,” he said. “Just recently, we had a housing project with a fire, and all those people were then not able to have a place to sleep that night. And so we had to scramble and find motel rooms, hotel rooms, families who would take them. If we had this emergency shelter, we could send them to that.”

Noland said he and other supporters also took partial responsibility for the issues at the armory and shared the lessons they’d learned. “Whenever adults or children aren’t supervised, sometimes they can get into trouble. And also you need to have rules. Rules that say you can’t be high, drunk, you know, impaired to be admitted to the shelter,” he said.

On Feb. 1 — roughly one year after the armory incident — the Marietta City Council voted to approve a resolution in support of the new emergency shelter, suspending the last two readings typically required for such actions.

It’s not yet clear when exactly the shelter will open. Bozian said they’re waiting on a grant she hopes will come through within 18 months. From there, she estimates it will take another six months or so to get everything set up. Organizers have already identified a building that can house 10 people with minimal renovations, and negotiations for that purchase are ongoing. The Washington County Homeless Project is also considering moving the drop-in center to the same location.

The new shelter will be located close to Marietta’s emergency services. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB]

According to Noland, the fact that the shelter wouldn’t be city owned or operated helped win over some of his reluctant colleagues. That, and a simple wording change.

“It’s no longer a warming center for homeless people,” Noland said. “Now it’s an emergency shelter. … We’ve removed the term ‘homeless’ from it.”

Hope

Sometimes it’s hard even for Gene to wrap his head around homelessness.

“You got people out, ‘Homeless, please help,’ and the next thing you know, you see ’em round the corner sticking a needle in their arm. I don’t — I never understood that,” he reflected. “But I can’t, you know — to each their own. Seen people starving, but yet, you don’t know their stories. I understand people do things to block out stuff; block the pain away, wish it’d go away. But it doesn’t. And they have to hide themselves in a bottle. I tried the bottle, multiple times. Didn’t get me nowhere but jail.

“I tried — yeah, I’ve done a few things in my day. I ain’t no saint by no means. But — you gotta live and learn. And it’s hard.”

Among the odd jobs Gene has done for food are yard work and detailing cars. Cars in particular are a source of enjoyment. He’s a fan of anything that goes fast.

When he learned about the Washington County Homeless Project, his initial reaction was one of mistrust.

“It’s hard finding help if you’re stuck. People that actually give a s***. Not just, they’re doing it because they had a — something on their conscience wasn’t right, so they decided all the bad stuff they did, they’d do one good thing and try to be happy with that,” he said.

Despite Gene’s reservations, the site supervisor at the drop-in center, Kelly Hendershot, won him over. She helped him pay off his outstanding fines and get his driver’s license back.

From left: Christy Biehl, Susan Arnold, Kelly Hendershot and Robin Bozian of the Washington County Homeless Project. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

“All in all, these women here, they really do need to be praised for the stuff that they put up with and do for us,” he said.

The simple fact of having a place to shower and eat has left a strong impression on Gene. Other places in Marietta aren’t nearly so welcoming, and he carries that sense of rejection with him.

“This town was made with these old-timer baby boomers. And if you don’t fit into their plan, they don’t want you here. Period,” he said. “If you’re homeless, they don’t want nothing to do with you.”

With the limited resources at their disposal, the workers at the drop-in center can’t solve homelessness itself. Instead, they do their best to chip away at the edges.

“There’s always hope,” Bozian said. “So what we try to do is figure out, where can we help them find a little hope? … What we try to do is, ‘OK, let’s break it down. Let’s start with a little something and get little, little successes.’”

Gene glances at the warm food Bozian and Hendershot are preparing to serve visitors at the drop-in center. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

For example: Getting Gene his driver’s license.

“They made phone calls for me, and they actually got hold of somebody that I couldn’t,” Gene recalled. “Every time I called, I’d get put on hold, I’d get told to go online to do this. I don’t know how to do that s***. … I can make a car run. When it comes to all that electronic bulls***, I don’t — I know how to make a phone call.”

Once, this kind of obstacle might have derailed Gene’s efforts. Now, he’s looking forward to the day he can drive again.

“I’m actually trying to go north,” he said. “I wanna go up to where my mom was born and see my cousins. I actually got some family up there that actually do care.”