This three-bedroom, two-bath home on East State Street in Athens — with a detached single-car garage and a shared driveway — was recently listed for sale at $450,000. An offer came in after the second showing. Home prices in the city and throughout southeast Ohio have risen fast, and the relatively small number of homes that go on the market often do not last long. [David Forster | WOUB]

Home prices in southeast Ohio are far outpacing wages, leaving even middle-income workers behind

Homebuyers in Athens County and throughout the region are caught in a market in which demand for homes far exceeds the supply and prices have risen sharply. Building more homes is the obvious answer, but it’s not that simple.

Amber and Regis Saxton are looking to buy a house in Athens, where Amber spent much of her childhood. She and Regis both graduated from Ohio University, and the couple have fond memories of the college town.

“So we wanted to move back because it feels like home to us,” Amber said.

But finding a home has proven challenging, even with their $275,000 budget.

“All we’re looking for is a solid house,” Amber said. “That’s what we want — just something solid that we can renovate and put our money into, but that is not super toxic, and that is not falling down a hill, and that is not in a flood zone, and that is not full of mold.”

That may seem like a modest request, but not in this market.

Amber and Regis, and other would-be homebuyers in Athens and throughout southeast Ohio, are caught in a market in which demand for homes — especially affordable ones — far exceeds the supply and prices have risen sharply.

“Shortage of affordable housing is really the problem, but why there’s a shortage of affordable housing is super complicated,” said Andy Stone, service-safety director for the city of Athens.

And there it is: It’s complicated.

This is the first in a series of stories about how what is widely considered a national housing crisis is playing out in southeast Ohio. Sources trying to explain the confluence of factors that created and perpetuate this crisis almost invariably resort to saying, simply, that it’s complicated.

Regis and Amber Saxton recently moved to Athens from Virginia to continue their search for a house to buy. They have found few good options in their price range. [Shamar Semple | WOUB]

The stories in this series will each take a piece of this complicated problem and explain not just what role it plays on its own and in combination with the other pieces, but also what changes might be made to improve the situation.

The first thing to understand is the crisis in housing, and affordable housing in particular, is not new. It’s been building for years, and in some ways for decades. And it doesn’t appear it will be over any time soon.

“When people say, hey, I think we’re experiencing a housing crisis, those of us in the business go, where have you been?” said Chris LaGrand, a senior vice president with Woda Cooper, a Columbus-based company that develops affordable housing in more than a dozen states. “I mean, we’ve been experiencing a housing crisis for the last five years. It’s worse now than it was back then and it’s getting worse, and the dynamics look like they’re just going to continue to get worse.”

These dynamics include the high cost of land suitable for development; high labor costs driven in part by a severe shortage of skilled workers in the construction trades that has only worsened since the pandemic; the high cost and in some cases long lead times required to get basic construction materials, another consequence of the pandemic but also a result of global trade policies; difficulties lining up financing for housing developments, especially affordable housing; and old zoning codes that make it difficult to build in the modern landscape, creating uncertainty, causing delays and driving up costs.

In other words: It’s complicated.

It’s a supply problem

In early March, Ohio University was seeking applications for a senior assistant registrar. The position required a bachelor’s degree, with a master’s preferred, at least six years of related experience and at least three years of supervisory experience. The salary range was $58,972 to $68,556.

This is among the better-paying jobs in Athens County, well above the average wage even at the low end of the salary range.

But it’s likely not enough, even at the top of that range, to buy a house in the city of Athens at $258,250, the median sales price for 2023. Not without a 20 percent down payment — that’s $51,650 — and some way to secure a below-average interest rate.

The job might be enough to buy a home outside the city: The 2023 median sales price for Athens County overall was $215,000. But it will depend on where the salary lands inside the range, the size of the down payment and the interest rate.

(These scenarios assume that no more than 28 percent of that monthly salary will be spent on the mortgage plus property taxes and insurance. This is the standard for what is considered financially prudent and lenders will be looking at this when deciding whether to approve a home loan. Some lenders might not approve a loan that will consume more than 28 percent of a buyer’s income.)

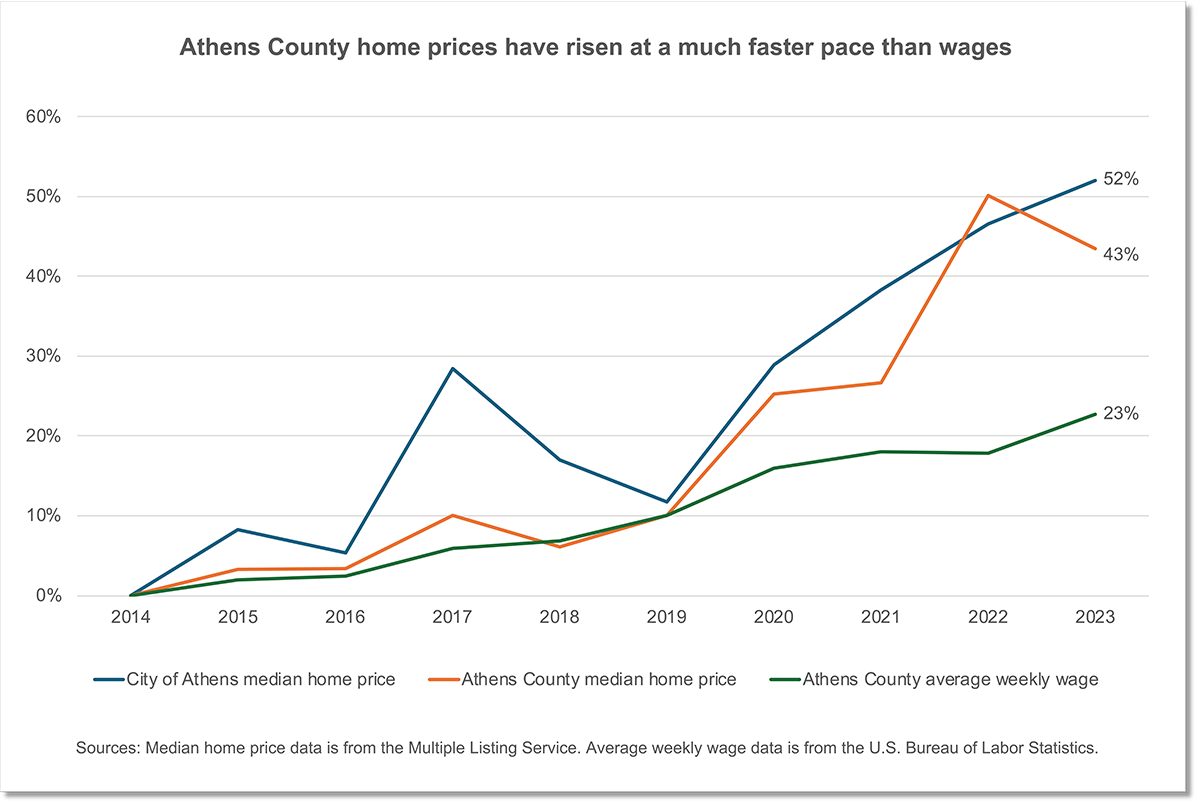

The cost of a single-family home has risen much faster than wages.

The 2023 median sales price for the city of Athens is up 52 percent from $169,900 in 2014. The median for Athens County overall is up 43 percent from $149,900 in 2014. (The median sales prices are drawn from the Multiple Listing Service, which real estate agents use to list homes for sale.)

Meanwhile, the average weekly wage in Athens County has risen 23 percent since 2014 — about half as much as home prices, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. It was $747 in 2014 and $917 in the third quarter of 2023, the most recent data available. This works out to $47,684 a year.

This figure is likely skewed a little high by some of the higher wages at Ohio University, the largest employer in Athens County and the surrounding area. Based on a review of jobs posted on the online job board Indeed over the past several months, most jobs in the Athens area offer wages well below the average.

The bottom line is that home prices today are much farther out of reach of the average wage earner than a decade ago. More residents, including professionals working at jobs that require college degrees, are simply finding themselves priced out.

It now requires close to $90,000 a year in income to buy a median-priced house in the city of Athens with 5 percent down — nearly double the average annual wage.

Interest rates were much lower a decade ago than they are now, averaging 4.17 percent in 2014. But even if rates dropped back to that level, the median-priced house would still be far out of reach for the average wage earner.

This is a point Jay Pascoe, executive director and chief operating officer of the Ohio Mortgage Bankers Association, made in testimony before the Ohio Senate Select Committee on Housing, which was created last year to examine the housing crisis and has held hearings throughout the state.

“While they certainly can impact what a potential homeowner can afford, interest rates are not the No. 1 driving factor in the current housing market,” Pascoe said. “That accolade belongs to affordability, or availability, or lack thereof.”

It’s a supply problem, he said: “We simply are not building enough homes that working-class Americans can afford whether they are single or a family.”

New housing starts in Ohio have dropped more than 40 percent from where they were 20 years ago, Enzo Perfetto, president of the Ohio Home Builders Association, told the Senate committee at a hearing in January.

This lack of supply drives up prices. And so more and more people are finding themselves priced out of buying a home.

“I think in the past, people have thought affordable housing is for the very, very poor,” said Jennifer Walters, president and CEO of Fairfield Homes, an affordable housing developer based in Lancaster. “And finally, I think there is now becoming an awareness of: Affordable housing is a very big band of people.”

The home ownership rate in Ohio was 70 percent in 2020. By the end of 2022 it had dropped to 64 percent — lower than the national average, then at 66 percent, for the first time on record, according to the 2024 Ohio Housing Needs Assessment produced by the Ohio Housing Finance Agency.

Since 2020, Ohio’s housing stock has grown by 0.9 percent, less than half the national growth rate, according to the OHFA report. Over this period, central Ohio has seen the most housing growth at 2.4 percent, while southeast Ohio has had the slowest growth rate at 0.2 percent.

Meanwhile, fewer existing homes are going on the market, further constricting the supply of homes for sale and helping drive up prices. Those who own a home with a comfortable mortgage at a low interest rate may be reluctant to give that up and instead stay put until interest rates or prices, or both, start to drop.

In the city of Athens, 158 single-family homes sold in 2023, the lowest in a decade and a 23 percent drop from 206 homes the year before, according to data from the Multiple Listing Service. Athens County overall saw the same decline: The 255 single-family home sales in 2023 was also the lowest in a decade and 23 percent lower than the year before.

But even those homeowners who are staying put will still feel the pinch of higher home prices. The latest assessment by the Athens County auditor’s office found property values up 20 percent across the board from three years ago. And this means higher property taxes.

‘A totally different world’

It’s a tough market even for those who can afford to buy a home.

“I started doing real estate in 2010,” said Ally Rapp Lee, a broker with Athens Real Estate Co. “So at that time, it was not uncommon for homes to be on the market for three months, six months. I could have a buyer and we could look at 10 or 15 houses. They could go back for a second look, spend tons of time considering their options, make an offer, and then negotiate that price down. It’s a totally different world now.”

Homes are selling much more quickly now, some in as little as a day or two, and in some cases for more than the asking price. The expectation is that buyers are making their best offer up front because there’s often no chance for negotiation, Rapp Lee said. Sellers are unlikely to come back with a counter offer if they already have, or expect to soon have, multiple offers on the table.

This puts a lot of pressure on buyers, especially those who may be pushing their budgets to the limit to get a home.

“People need time to process, to run the numbers, to make sure that the purchase is going to be a wise one for them financially and for their family in the future,” Rapp Lee said. “But then what if you have 48 hours to make a decision? You have one chance to see that house, maybe less than an hour to spend. And your agent tells you, ‘I’m sorry, there are two other offers, four other offers. You need to decide to make an offer within the next 24 hours or lose out on this house.’”

Athens real estate broker Don Linder said some buyers are putting down large nonrefundable deposits to make their offers more attractive in this competitive housing market. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

To sweeten their offers, buyers are taking risks.

Some are offering more than the listing price, and some are including an escalation clause so that if someone else comes along and offers more, their offer automatically goes up.

But a lender typically isn’t going to loan more than what a home appraises for, so some buyers are agreeing up front to pay any appraisal gap: the difference between their offer and the appraised value.

Some are waiving inspections, agreeing to take the home as is. “We’ll just take the risk that something’s wrong with the house because maybe it won’t be that bad,” Rapp Lee said.

And some buyers are putting down nonrefundable deposits.

“Which means that you basically give the seller a check, and if you don’t end up buying the house, they keep it,” said Don Linder, a broker with Berkshire Hathaway in Athens. “I’ve had people put 10,000, $30,000 non-refundable because they really wanted a house, which means they’re putting that money at risk. Believe it or not.”

Linder and Rapp Lee said they don’t necessarily recommend buyers take these risks, but they do make them aware that these are options that can help them lock down a home in a tight market.

These options clearly favor buyers with deeper pockets and make it tough for even those with moderate incomes to compete.

“Entry-level buyers almost have no possibility of buying a house at this point in time because there’s going to be others that are going to compete and take ’em out of that competition for houses that we’ll call affordable,” Linder said.

‘Affordable’ homes with issues

While residents working in Athens County increasingly find themselves priced out of buying a home, the region is attracting more people from other states with much higher costs.

Rapp Lee said she is seeing more out-of-state buyers who can work remotely coming in.

“Those are generally people who have some connection with the university or some family in the state who know what Athens offers in terms of its natural beauty and the community here and who think, ‘OK, Athens is great. I want to live near here,’” she said.

This perfectly describes Amber and Regis Sexton, the couple at the beginning of this story. The two have good-paying jobs at George Mason University in Fairfax County, Virginia, and have been working remotely since the onset of the pandemic.

They moved from pricey Fairfax County to the smaller and more affordable Richmond, Virginia, but the costs there keep rising.

“We keep getting chased away from areas because the rents keep going up,” Amber said. “And so that’s part of the reason we were looking into buying a home.”

The couple want to live in Athens within walking distance of the uptown area. The city’s median home price is within their budget, but what they soon found was that even homes around that price may still need a lot of work.

The housing stock in southeast Ohio is among the oldest in the state, which presents even more challenges for buyers. Homes with plumbing issues, electrical issues, roof and siding issues, and any number of other problems, may not pass an inspection.

This is a problem for those trying to get a loan through the Federal Housing Administration or through the Veterans Administration. These loans offer more favorable terms — such as lower down payments and attractive interest rates even with lower credit scores — that especially help moderate and low-income buyers.

In this market, sellers may have little incentive to address problems flagged during an FHA or VA inspection. They can sell instead to the next buyer in line with a conventional loan that doesn’t require the home to pass an inspection.

So homes that still seem somewhat affordable in this market may come with costly problems that put them out of reach for many buyers.

“In touring properties to buyers coming in from outside of the area, a common complaint is that these houses are rough, these houses have deferred maintenance, and that’s across the board,” Rapp Lee said. “I think it’s the old housing stock, and I think it’s the cost of materials, lack of available contractors — all that has contributed to folks putting off maintenance when it’s needed.”

Athens real estate broker Ally Rapp Lee said not too long ago buyers had time to look at multiple homes and consider their options before making an offer. “It’s a totally different world now,” she said. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

Amber and Regis are looking at homes from around $225,000 to $275,000. Their agent toured the homes with them on a video call from their apartment in Richmond.

So far, all of the homes have had problems they didn’t want to take on or would be too costly to repair.

In one, the floors were sagging at the corners and creating gaps between the floor and wall because the foundation is sinking. One needed an immediate roof replacement. Another was so infested with mold their agent had sinus problems the rest of the day. Another reeked of open sewage or a natural gas leak.

They hired a contractor to start going out with the agent so they could get a better idea what the issues were.

“It just kept being so bad that we needed somebody to tell us this is a five-grand problem, or it’s a 50-grand problem,” Amber said.

The estimates so far are all on the higher end.

“It’s going to need at least 50,000 to $80,000 worth of work for a home that’s already 225, 250 just at the purchase price,” Regis said.

The couple are now looking into a loan program that allows buyers to borrow enough not just to buy the home but also fix some of the problems. But the total loan amount still cannot be more than what they are qualified to borrow, so the higher the home price, the less they can afford to spend on repairs.

Amber and Regis finally decided the whole process would be a lot easier if they were in Athens already, so they found an apartment and in mid-March moved to town, with the hope that eventually a home in their sweet spot will turn up.

“What makes it particularly challenging for the city of Athens is that we have basically overinflated prices for our housing stock,” said Mayor Steve Patterson. “And it’s largely because we’re a university town. We have a lot of rental units that used to be homes that have a higher land value than they probably should have.”

This is another challenge that buyers like Amber and Regis face. Ohio University saw record enrollment this school year and is on track for a similar number in the fall. This creates more demand for student housing in a city where about 75 percent of the housing units are already rentals.

Buyers who plan to make the home their own may be reluctant to stretch their budget to buy a place they feel needs a lot of work to be livable. But an investor may look at the same home and figure it’s good enough for a rental, or it may only need a few repairs to meet the city’s minimum standards for rental housing.

Homes in Athens can be rented to students at the going rate of $500 to $600 a room. This further reduces the supply for buyers looking for a home to live in, which drives housing costs even higher. It also makes it challenging for nonstudents who cannot afford to buy a home to find a rental they can afford.

Just build more, right?

The housing shortage is at all price points, not just on the affordable end of the spectrum. And this creates a domino effect that makes the situation even worse for moderate and lower-income buyers.

Jesse Roush, executive director of the Southeastern Ohio Port Authority, the economic development agency for Washington County, explained how it works:

“The person who can afford 500,000 can’t find it, so they buy 350. The person that likes 350 can’t find it, so they buy 225. The 225 person has to buy 150. We don’t even really have a lot of those left anymore. If it’s 150, it’s a rental. So now all of a sudden they couldn’t buy one, they’re like, the heck with it. We’ll just rent for the time being.

“It blows my mind the number of dual-income working parents I know who are renting, who could afford a mortgage, who could have afforded a mortgage when it was two and a half, 3 percent, probably could still afford it at seven and a half, 8 percent, but they can’t find anything.”

“All of a sudden we woke up and there’s not enough housing, and there’s also not enough people to build it, and the costs are through the roof, and interest rates are high, and it takes just as long as it did before from start to finish,” said Jennifer Walters of Lancaster-based Fairfield Homes. [Walker Smith | WOUB]

The obvious solution is to build more homes for buyers at all income levels. Even adding higher-end homes should help with the affordability problem as people moving up to more expensive housing free their homes up to those in the income bracket just below them and so on down the line.

But it’s not so easy.

“It just goes back to all of a sudden we woke up and there’s not enough housing, and there’s also not enough people to build it, and the costs are through the roof, and interest rates are high, and it takes just as long as it did before from start to finish,” Jennifer Walters of Fairfield Homes said. “And so it just is a perfect storm right now. We’ll get through it, but it isn’t as simple as saying, we need affordable housing and we support affordable housing in our community, so come build it.”

Meanwhile, the housing deficit continues to grow. Ohio needs about 45,000 new housing units a year to keep up with demand, Vince Squillace, executive vice president of the Ohio Home Builders Association, told the Senate Select Committee on Housing at a hearing last year.

The last time the state saw this number of housing starts was nearly two decades ago.

From 2000 to 2005, starts ranged from a low of 47,700 to a high of 52,000. As the housing market began to cool in 2006 and then collapsed in 2008, starts plunged, sinking to 12,600 in 2009. They have slowly crept up since then, reaching 30,000 in 2021, but then dropped a bit over the past two years.

“As you can see, Ohio loses ground each year,” Squillace told the committee.

Against this backdrop, some of the world’s largest technology companies are investing heavily in central Ohio, buying up hundreds of acres, building new facilities, expanding existing operations and adding employees. Intel’s chip making plant under construction on the outskirts of Columbus is expected to employ several thousand people when fully built out in the coming years.

“If you start to look at what Columbus is going to need to add for these Intel investments and how many units, it looks almost insurmountable,” said Chris LaGrand of Columbus-based housing developer Woda Cooper. “There is just not a lot of appetite right now in the private home building sector to go out and build spec homes and to build up a supply of homes.”

“You just can’t do it. The pricing doesn’t work,” he said. “They can’t get the financing to make that work. And that’s a problem that’s going to create problems for communities everywhere as there’s this lack of single-family availability.”

Building a home is much more expensive than it was just a few years ago.

Ron White, who has been building homes in Athens County for several decades, said that five years ago he could build homes working-class people could afford. But not today.

“Man, it’d be hard to do,” he said. He might be able to build a modest three-bedroom, one-bath home for about $175,000, although $200,000 is a more realistic number. This is already well beyond the reach of someone earning the average income in Athens County, and it doesn’t include the cost of the lot and site development, which can add tens of thousands of dollars to the total.

Even nonprofit developers are struggling to keep housing affordable. Kenneth Oehlers, executive director of Habitat for Humanity of Southeast Ohio, said he’s still able to build homes for the low-income families his organization serves only because about 85 percent of the labor is volunteer.

Even so, it still costs around $125,000 to build a three-bedroom, one-bath home, on top of the cost of the land and site development, which has also risen significantly over the past few years, Oehlers said.

“Before you even put a shovel in the ground, you’re $50,000 in the hole,” he said.

“There is just not a lot of appetite right now in the private home building sector to go out and build spec homes and to build up a supply of homes,” said Chris LaGrand of Columbus-based housing developer Woda Cooper. “You just can’t do it. The pricing doesn’t work.” [Robb McCormick Photography]

Without free labor or some kind of tax credit or subsidy, it’s nearly impossible to build affordable housing given all the headwinds driving up costs, said Becky Eddy, chief community development officer for Integrated Services for Behavioral Health, a nonprofit that serves central and southeastern Ohio.

Integrated started developing rental housing in Athens County about a decade ago to provide its clients with more affordable options.

“If we’re talking specifically about growing the affordable housing stock, at least on the lower end of affordability, then you have to bring in some kind of subsidy to make up the difference between what that population can afford and what it costs you to build,” Eddy said. “It sounds great and altruistic to just build something and rent it out for less, but if you don’t have a way to pay the bills, you can do that once and then you’re gone.”

But even with a subsidy it can be difficult to make the math work. Government subsidies may require homes or apartments to meet certain environmental and accessibility standards that address real issues but make it even more costly to build housing that’s intended to be affordable.

Subsidies are also very competitive. There’s only so much to go around, and the scoring criteria tend to favor urban areas over rural, said Chasity Schmelzenbach, executive director of Buckeye Hills Regional Council, which promotes economic development in southeast Ohio. And any given subsidy may not cover the entire financial gap, requiring more subsidies or other sources of funding to make the project pencil out, which again puts poorer rural communities at a disadvantage.

Rents are up too

The shortage of affordable homes to buy leaves more moderate and low-income people with no choice but to rent. But rents are rising as well.

Statewide, rent is higher than in any year on record other than 2021 when adjusted for inflation, according to the 2024 Ohio Housing Needs Assessment prepared by the Ohio Housing Finance Agency.

And the percentage of income spent on rent is increasing, according to the report. People who spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing are considered at risk of being unable to afford other necessities, such as food and healthcare, or unable to cover an unexpected cost. In 2021, 25 percent of Ohio renters were spending at least half of their income on housing, putting them at greater risk of eviction and homelessness.

Meanwhile, the state has a severe shortage of rental housing for its lowest-income residents. There are 444,768 extremely low-income households in Ohio, but only 177,386 rental units that are affordable and available to them, according to a new report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. This is a deficit of 267,382 units.

A review of listings in the Athens County area shows renters can expect to pay at least $900 a month for a two-bedroom house or apartment and at least $1,200 a month for a three-bedroom unit. At these prices, it would require $36,000 in annual income to afford a two-bedroom rental and $48,000 for a three-bedroom in order to not spend more than 30 percent of income on rent. This is well beyond the reach of anyone working even one of the better-paying retail or service jobs.

Cheaper housing can be found, but those with smaller incomes may find their only options are homes with significant, and in some cases dangerous, problems.

Outside the city of Athens, there is little regulation or oversight of rentals, meaning landlords in the county are free to rent just about anything in just about any condition.

“We’ve had issues where sewer lines aren’t connected,” said Oehlers of Habitat for Humanity. “We’ve had direct discharge of sewage into creeks that we’ve seen. We’ve seen people having to take showers in sinks because the bathtubs don’t work. The whole floor is completely missing in the living room.

“We’ve taken people out of houses where there literally is no water — there just aren’t water lines anymore that work. We’ve taken several people out of houses where they use their ovens as their heating source because the furnace is broke, and there is nothing else that they can use to be able to keep their house warm. … It’s crazy out there.”

Habitat for Humanity of Southeast Ohio has helped renters get out of homes without a heating source or running water or a place to bathe, said Kenneth Oehlers, the organization’s executive director. “It’s crazy out there.” [Walker Smith | WOUB]

Building more rental housing for low-income people would give them more and better options, but on top of all the other issues plaguing housing construction, affordable rental housing often runs up against zoning restrictions and opposition from neighbors.

To make these projects pencil out, it often helps to build them bigger. Costs for basic materials and labor are not cheaper just because a developer is building affordable housing, so spreading the cost over more units makes a project more feasible. This is especially true with affordable housing because the developer will be charging less rent for the units, so the return on the investment will be lower.

But many communities have zoning codes that strongly favor traditional homes over apartments and have strict height and density restrictions that make it difficult or impossible for the financing to work on a project. Or the developer may have to seek a zoning variance, resulting in delays and additional costs with no guarantee that in the end a variance will be granted.

Affordable housing developers also run into opposition from neighbors who don’t want these projects in their neighborhood.

“It can show up in a bunch of different ways and different flavors,” Chris LaGrand of developer Woda Cooper said of community resistance to affordable housing. “There are situations where we will take on a little bit of a challenging deal because we think there’s a reason to do that. And there are other situations where we go, yeah, we’re just going to pass on that one. We’re going to go someplace else.”

Pinching already tight budgets

Substandard housing isn’t just a problem for renters. People who already own homes are not immune to the housing crisis, especially those living in older homes in need of maintenance. Seniors and others living on fixed incomes in particular may struggle to keep up with repairs given the high costs of construction materials and labor and the other ways in which inflation is pinching their budgets.

Habitat for Humanity has a program in which it does home repairs and maintenance for low-income residents. This includes big projects, such as replacing roofs and heating and cooling systems. But the organization has been so overwhelmed with requests that in mid-February it had to temporarily stop taking applications.

“If you called me today and said I have a roof that needs to be replaced when could you get to it, I’d tell you I honestly can’t tell you,” Oehlers said.

Some people are able to pay Habitat for the repair work, but many cannot afford to and grants are used to cover the costs. Oehlers said he doesn’t have enough grant funding to take care of everyone reaching out for help.

Other agencies are also seeing more demand for services as rising costs for housing and other essentials further squeeze already tight budgets.

Hocking Athens Perry Community Action, better known as HAPCAP, administered a pandemic-relief program that provided funds to help people struggling to pay their mortgage or rent.

It expected to run out of funding by the end of last year but in January realized it still had some money left over. It began accepting applications again but in two days had to stop because it had already filled the 200 available slots. The rest were put on a waiting list.

HAPCAP has also seen a significant increase in the number of people coming to food pantries in its network. In 2023, the total number of children, adults and seniors was 59,028, the highest by far in at least 10 years, and a 45 percent increase over the number of visitors the year before the pandemic began.

Oehlers said many people come to southeast Ohio, among the poorest regions in the country, expecting to find affordable housing options. But increasingly that’s no longer the case. Which raises the question: If people here are finding themselves priced out of housing, what is the next move?

“I don’t have an answer. I don’t know,” said Athens real estate broker Ally Rapp Lee. “It’s a concern — understatement of the year.”